I recently stumbled upon an elementary problem: compute the intersection points of a line — actually, an affine function — and a rectangle. For that kind of simple geometric problem, I do not rush toward Google. I prefer to try to solve it myself, to keep my problem-solving mind sharp!

I made some drawings, found the corner cases, then an algorithm, and it was finished in no time.

I found the algorithm was simple and elegant, so I decided to check how it compared to other methods. Google led me to a Wikipedia list of algorithms solving this problem. I discovered that my solution was very close to Liang-Barsky algorithm apart from the fact that I was working with an infinite line when other methods are dealing with finite segments.

I was, however, surprised to see that the explanation of the algorithm was way more complicated than the naive intuition I had in mind when solving the problem myself. Here is an attempt to explain how I see Liang-Barsky algorithm and how to code it with 3 lines of Python.

Note: That kind of geometric operation is typically used in graphics engines. In this context, the implementation needs to be as efficient as possible and leverage all kinds of tricks to be faster. The goal of this post is to focus on intuition and understanding rather than efficient implementation.

The problem

Let’s put some letters on the problem. I have an affine function parametrized by \(a\) and \(b\) that can be written as:

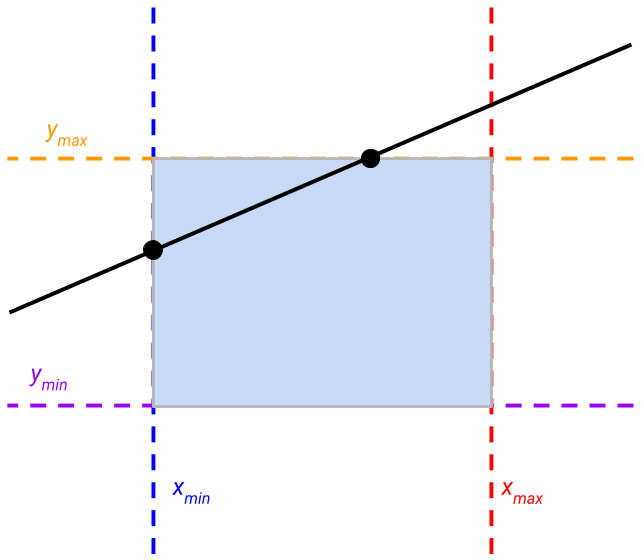

\[f(x) = ax + b\]And a rectangle define by two points: \([(x_{min}, y_{min}), (x_{max}, y_{max})]\).

On the figure, we see that the black line (our affine function) intersects with the rectangle when it crosses the vertical line \(x_{min}\) and the horizontal line \(y_{max}\). The tricky point is that our function can cross any of the sides of the rectangle, and therefore we need to determine the ones in which we are interested. This is what the Liang-Barsky algorithm does.

Warning: A perfectly horizontal or vertical line is parallel to some of the rectangle sides. This known corner case is traditionally treated apart because its solution is straightforward. I did not mention it here to keep the code as simple as possible.

The algorithm

Our affine function being infinite, it necessarly crosses all the sides of the rectangles — if we consider them infinite too. We have therefore 4 intersections, with \(x_{min}\), \(y_{min}\), \(x_{max}\), and \(y_{max}\). But only two of them are actually on the sides of the rectangle.

Liang-Barsky’s algorithm tells us how to determine these two. And the intuition is very simple: Given all the intersecting points, if we consider them sorted by their \(x\)-coordinate, the first and last points are always outside of the rectangle. And that’s it!

This intuition is easy to verify on the example above: In order to cross the left side of the rectangle, the affine function must be between \(y_{min}\) and \(y_{max}\), so it necessary crosses one them before, in this case, \(y_{min}\). You can try all the different cases as an exercise: It always works.

Note: The cases where the affine function is parallel to the sides of the rectangle, where it crosses exactly a corner of the rectangle (so two sides at once) can be handled separately. I also assume here that the line crosses the rectangle. A simple trick can test this. Looking at the first two points, sorted from left to right again, one of them must cross a \(y\)-line, and the other an \(x\)-line, in any order. If the line cross two \(x\)-lines first, it means that it is evolving in the domain above or below the rectangle for the rest of the graph.

The code

Let’s now code it! Using the sorted function of Python, this is trivial!

def line_x_rectangle(a, b, x_min, y_min, x_max, y_max):

# Intersections of f(x) = ax + b with the rectangle. (x, y, axis)

p1, p2 = (x_min, a * x_min + b, 'x'), (x_max, a * x_max + b, 'x'),

p3, p4 = ((y_min - b) / a, y_min, 'y'), ((y_max - b) / a, y_max, 'y')

# Python sorts them using the first key

p1, p2, p3, p4 = sorted([p1, p2, p3, p4])

# Check if there is an intersection, returns the points otherwise

if p1[2] == p2[2]:

return None

return p2[:2], p3[:2]

Why is that beautiful?

I would say that this algorithm is beautiful because it relies on a simple principle that is intuitive. It can be written in a clear and concise code — thanks to some Python magic.

Now that you have this intuition in mind, I invite you to take a look at the Wikipedia implementation and it should appear clearer. Do not hesitate also to compare this explanation to other available on the web, it is always better to find the explanation that better suits you.